Three millennia of storytelling at the Morgan, Goya’s visions of war, Alison Nguyen’s diasporic tale, and Indigenous artistry in every medium imaginable.

Lisa Yin Zhang, Valentina Di Liscia

February 9, 2026

— 6 min read

Lisa Yin Zhang, Valentina Di Liscia

February 9, 2026

— 6 min read

A visitor admires a Roy Lichtenstein print and a c. 1700 folio from a Ramayana as part of Come Together: 3,000 Years of Stories and Storytelling at the Morgan Library (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

A visitor admires a Roy Lichtenstein print and a c. 1700 folio from a Ramayana as part of Come Together: 3,000 Years of Stories and Storytelling at the Morgan Library (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. Joan Didion, a New Yorker, famously said this. The exhibitions we recommend you trek out to see — and it’s a high bar, given these subfreezing temperatures — center that age-old practice. A show on storytelling at the Morgan Library & Museum, with a 3,000-year scope, should prime you well for those that follow. Explorations of the legacy of national revolutions form the basis of Goya’s depictions of the savagery of the Spanish War of Independence in the 19th century as well as Alison Nguyen’s tracing of the unexpected currents of Vietnam’s war for liberation in the 20th. Two shows offer very different ways to tell the contemporary tale of Indigenous art-making in the Americas, one a rich showcase of glassware in the United States starting in the 1960s, the other a look at the makers in the many nations and cultural groups whose land intersects the Amazon.

I’m struck by the ways these stories interlace this very city. New York’s City Hall can be seen in the background of one of Nguyen’s films; the Amazonia showcase is housed in a policy center; and the glasswork presentation is in the former New York Customhouse, still a government building. It's a reminder to stay grounded in this particular land, history, and time, even while reaching toward abstractions and speculative futures. There’s always a story to tell.

—Lisa Yin Zhang, associate editor

Come Together: 3,000 Years of Stories and Storytelling

Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue, Murray Hill, ManhattanThrough May 3

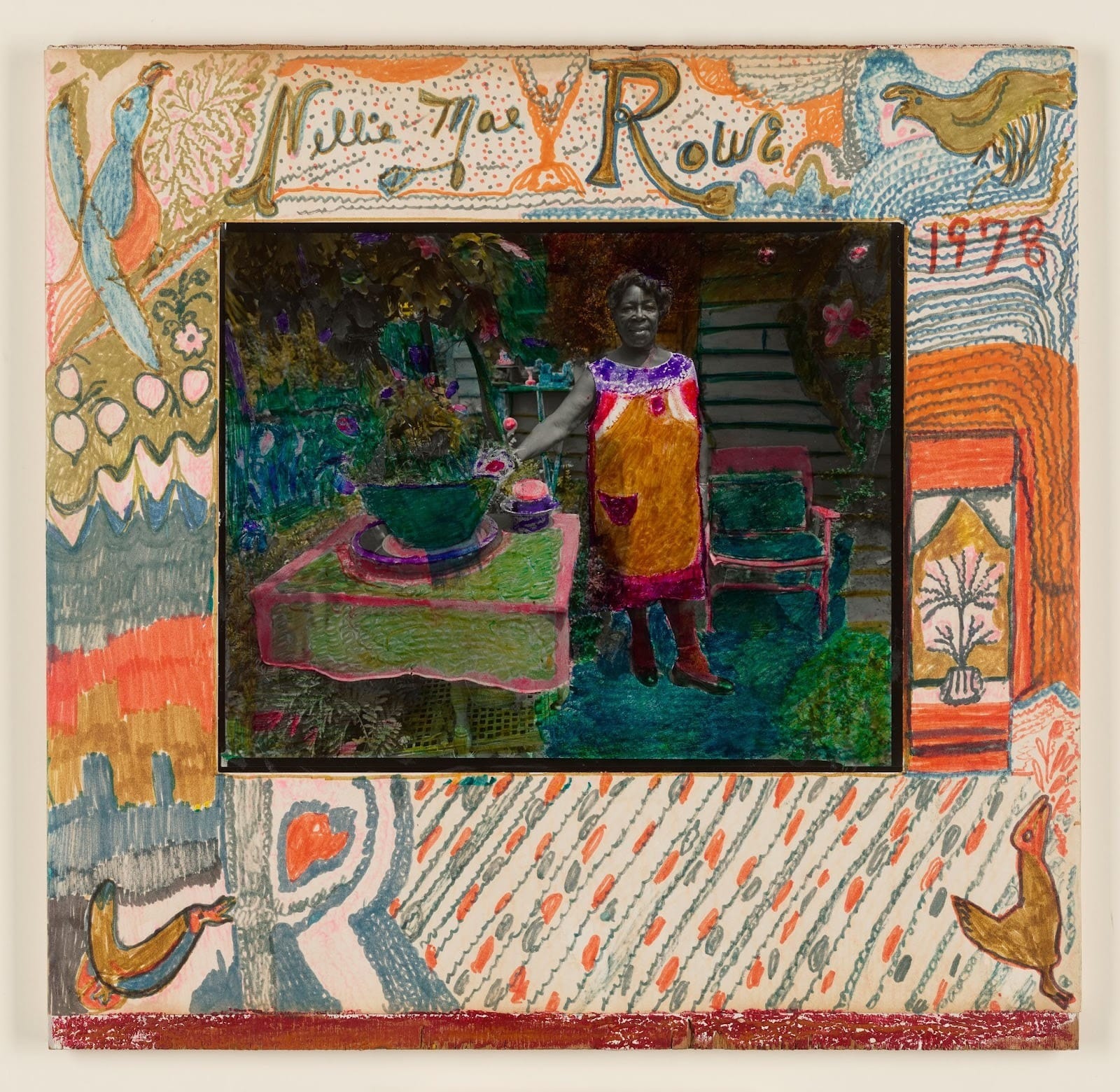

Nellie Mae Rowe, "Untitled" (1978) (© 2026 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo by Janny Chiu)

Nellie Mae Rowe, "Untitled" (1978) (© 2026 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo by Janny Chiu) What do Nellie Mae Rowe, Babar the Elephant, and an 18th-century illustration of an ancient Indian epic have in common? According to this exhibition, all three — plus over 140 other objects primarily drawn from the Morgan’s collections — grapple with the possibilities of storytelling and mythmaking. Because the show takes a broad view of its theme, the connections can be tenuous: A woodcut by Faith Ringgold, whose “story quilts” are a magnificent example of narrative traditions, hangs near Peter Hujar’s iconic Gay Liberation Front poster photograph, an arguably unexpected selection. The upside of this encompassing approach is the realization that our instinct to share histories and spin allegories across generations is not confined to tales, fables, and legends, but an integral part of our universal human experience. —Valentina Di Liscia, senior editor

Goya and the Age of Revolution

Hispanic Society, Washington Heights, ManhattanThrough June 28

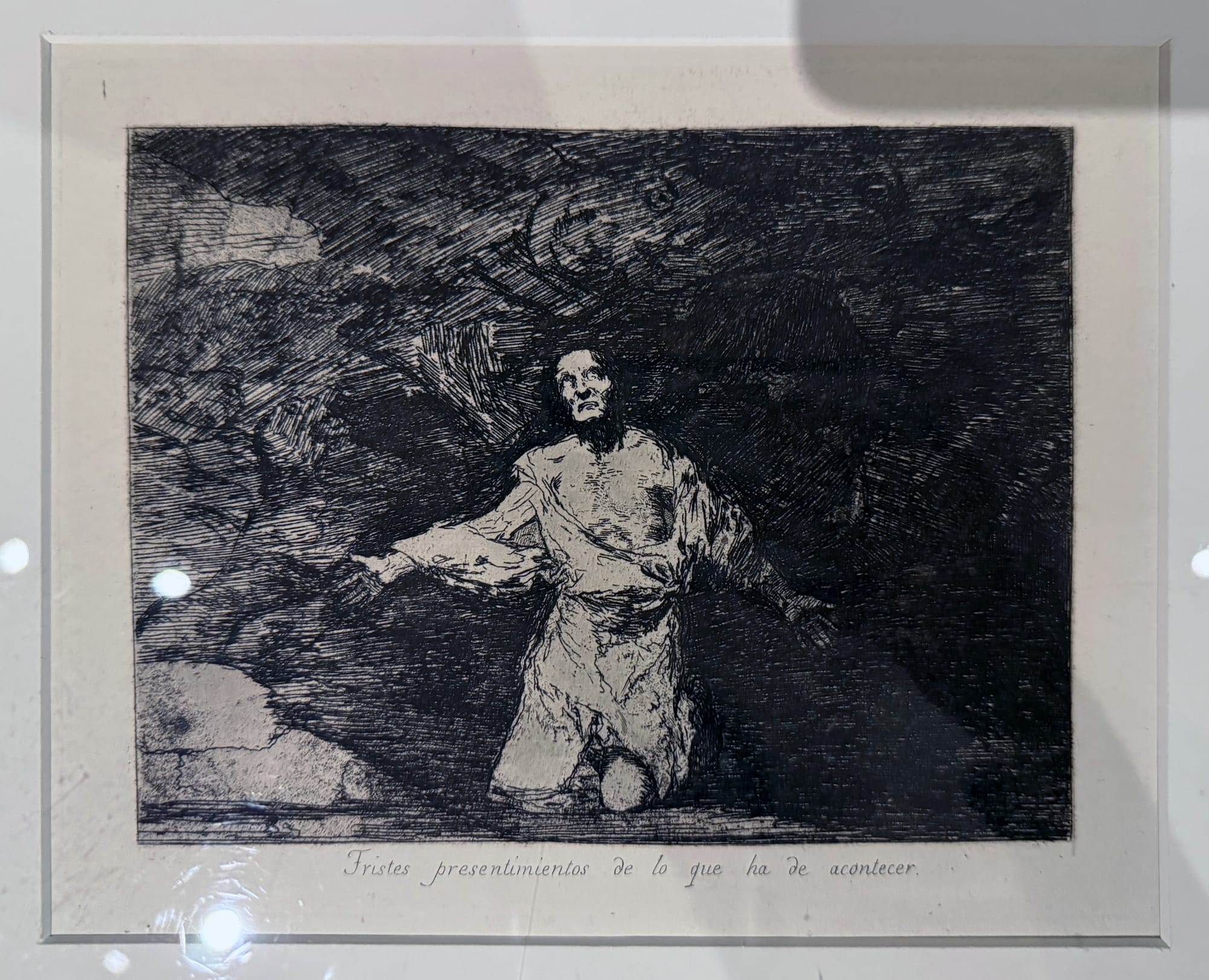

Francisco Goya, "Tristes presentimientos de lo que ha de acontecer" (Sad premonitions of what is to come, 1812–20), etching (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)

Francisco Goya, "Tristes presentimientos de lo que ha de acontecer" (Sad premonitions of what is to come, 1812–20), etching (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)This year marks the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, but that event affected far more than the United States. Supported by Spain and France, it inspired the French Revolution of 1787–99. This led to the rise of Napoleon, who invaded Spain in 1808, launching the Spanish War of Independence. Francisco de Goya would go on to capture the destruction of this war in his Disasters of War series (1810–20) — 82 posthumously published prints that focus on its aftereffects. Multiple large-scale, full-length oil portraits of officers and generals by the Spanish artist are also on view, but it is these prints that are the most devastating. In one, a figure is brought to his knees as darkness presses down on him. The caption reads, “Tristes presentimientos de lo que ha de aconter” (Sad premonitions of what is to come). In a time of escalating tensions, may we take such a warning to heart. —Lisa Yin Zhang

Alison Nguyen: Perforation, Ellipse

Storefront for Art & Architecture, 97 Kenmare Street, NoLita, ManhattanThrough March 28

Installation view of Alison Nguyen: Perforation, Ellipse (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Alison Nguyen: Perforation, Ellipse (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)Plaintive and yearning bolero music emanates from multiple screens pinned to wheeled metal armatures. It’s played by a middle-aged woman with a mic and about a million filters, and a fuckboy in a tuxedo trying to make what appears to be a thirst trap, and starts and stops abruptly, spliced with clips of flickering abstract shapes or the words “SCENE MISSING.” The musical genre was suppressed by the Vietnamese government in the wake of what they call the American war, but it was nurtured underground and abroad. The unpredictable, funny, and devastating ways that history alchemizes with the present seems to be the central thread of this exhibition. “Interest goes up? We starve in Nigeria,” one screen reads. Fitting, then, that the central video depicts the artist firing arrows from a crossbow with Manhattan’s City Hall in the background. What’s a couple of measly arrows against the levers of the state? It’s not nothing. What arrows are trailing through time as we speak? —Lisa Yin Zhang

Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass

National Museum of the American Indian, 1 Bowling Green, New York, Financial District, ManhattanThrough May 29

Angela Babby, "Melt: Prayers for the People and the Planet" (2019) (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)

Angela Babby, "Melt: Prayers for the People and the Planet" (2019) (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)This isn’t a huge show, but it’s a confident one. It conveys the breadth of Indigenous glass-making since the advent of the Studio Glass and Contemporary Native Art movements in the 1960s. While most works come from the Southwest and Pacific Northwest, the show suggests that these are but a sampling of an even vaster landscape. It opens with a waterfall of clear glass glyphs that looks like a transparent, three-dimensional Keith Haring work, followed by classic vessel forms and motifs recreated in glass, like Carol Lujan’s rippling take on Diné tapestries; stunning stained-glass portraiture by Angela Babby; and colorful sea animals by Marvin Oliver. Special tribute is paid to Dale Chihuly — though he wasn’t Indigenous himself, he established the first glass program at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts; 1970s vessels from that workshop are also on view. —Lisa Yin Zhang

Amazonia Açu

Americas Society, 680 Park Avenue, Upper East Side, ManhattanThrough April 18

Claudia Opimí Vaca, "Bajo el toborochi" (Under the toborochi, 2025), cotton fabric embroidered using an appliqué technique from the Tajibo community of the Bolivian Amazon (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)

Claudia Opimí Vaca, "Bajo el toborochi" (Under the toborochi, 2025), cotton fabric embroidered using an appliqué technique from the Tajibo community of the Bolivian Amazon (photo Lisa Yin Zhang/Hyperallergic)This exhibition was organized under an unusual framework — it was assembled by nine curators, each from one of the states the Amazon River cuts through. One of their names labels the corresponding wall text accompanying artists from their respective region. The introduction describes this approach as “kaleidoscopic,” and I can’t think of a more apt way to express the phenomenological experience of the show. Iconography and themes echo across works by different artists from multiple regions — jaguars, rubber, the magical properties of plants, to name just a few. A rich variety of media is on display, from the weaving of clay to the making of paper out of sugarcane and cotton. Even the translation of techniques and motifs from one medium to another can be seen: bodypainting traditions on paper, textile motifs on canvas. I was particularly drawn to a painting by Sara Flores in which a labyrinthine motif seems to uncoil before your eyes; the tightly wound mark-making of Hélio Melo (please, can someone get him a contract for a picture book?); and Claudia Opimí Vaca’s puffy, stitched appliqué tapestry. —Lisa Yin Zhang